JLR: Technique boosts omega-3 fatty acid levels in brain 100-fold

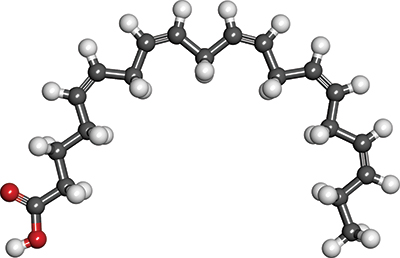

A ball-and-stick diagram of eicosapentaenoic acid, which has been shown to be effective in treating and preventing depression. SubDural12/Wikimedia Commons

A ball-and-stick diagram of eicosapentaenoic acid, which has been shown to be effective in treating and preventing depression. SubDural12/Wikimedia Commons

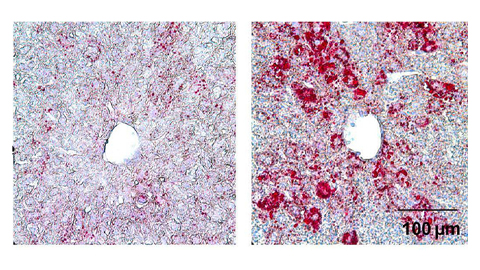

Getting enough docosahexaenoic and eicosapentaenoic acid, or DHA and EPA, into the brain to study their effects on conditions such as Alzheimer’s and depression — which they have been shown to help — is no easy task. While supplements containing these omega-3 fatty acids exist, there is scant evidence showing that the supplements actually increase DHA or EPA in the brain. To increase levels of EPA in the brain measurably, a person would have to consume a small glass of it each day, quite possibly with the side effect of smelling like fish.

Now researchers from the University of Illinois at Chicago report that adding a lysophospholipid form of EPA, called LPC-EPA, to the diet can increase levels of EPA in the brain 100-fold in mice. The amount of LPC-EPA in the diet required for this increase is rather small for mice — less than a milligram per day. The human equivalent would amount to less than a quarter of a gram per day.

DHA and EPA are known to have anti-inflammatory effects and protect against various neurological and metabolic diseases. DHA has been shown to be good for memory and cognitive deficits associated with Alzheimer’s disease, and, in studies, EPA has been shown to be effective in treating and preventing depression.

DHA is already prevalent in the brain, and there is little evidence to support the idea that eating lots of fish oil, either through whole fish or supplements, increases levels of DHA in the brain. EPA is found in very low concentrations in the brain, and boosting those levels through consuming EPA has proved difficult, because the amount that would need to be ingested to show increases in brain EPA levels is quite large — 40 to 50 milliliters daily. And researchers still don’t really have a great understanding of how EPA works to reduce depression and how much is needed in the brain to have these anti-depressive effects.

Papasani Subbaiah is a professor of medicine and biochemistry and molecular genetics in the UIC College of Medicine and corresponding author of a paper about the new work published in the Journal of Lipid Research.

“In order to do the trials to determine the proper dosage and how EPA works in regards to depression, we need to have a better way of getting it into the brain because you need to consume so much of it that it’s just not practical, at least for human trials,” Subbaiah said.

EPA provided in the form of lysophospholipid escapes the degradation by pancreatic enzymes that prevents the type of EPA in fish oil supplements from passing into the brain, he said.

“It seems that there is a transporter at the blood–brain barrier that EPA must pass through in order to get into the brain, but EPA in fish oil can’t get through, whereas LPC-EPA can,” Subbaiah said. “You don’t have to consume all that much LPC-EPA to have significant increases of EPA show up in the brain, so this could be a way to do rigorous studies on the effects of EPA in humans.”

Producing LPC-EPA is not difficult, and it can be incorporated into feed pellets that Subbaiah fed to laboratory mice. After eating 1 mg per day of the LPC-EPA in their feed for 15 days, these mice had up to 100 times more EPA in their brains than mice eating plain EPA. Interestingly, the mice eating LPC-EPA also had two times more DHA in their brains.

“This study is proof of the concept that we can increase levels of both EPA and DHA in the brain via supplements or by incorporating LPC-EPA in the diet,” Subbaiah. “Using this technique, we can now perform critical studies to see if increasing concentrations of these fatty acids in the brain can help prevent and treat Alzheimer’s and depression in mouse models, and then move into human trials if results are promising.”

This article is adapted from a press release produced by the University of Illinois at Chicago News Bureau.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition monthly and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

How a gene spurs tooth development

University of Iowa researchers find a clue in a rare genetic disorder’s missing chromosome.

New class of antimicrobials discovered in soil bacteria

Scientists have mined Streptomyces for antibiotics for nearly a century, but the newly identified umbrella toxin escaped notice.

New study finds potential targets at chromosome ends for degenerative disease prevention

UC Santa Cruz inventors of nanopore sequencing hail innovative use of their revolutionary genetic-reading technique.

From the journals: JLR

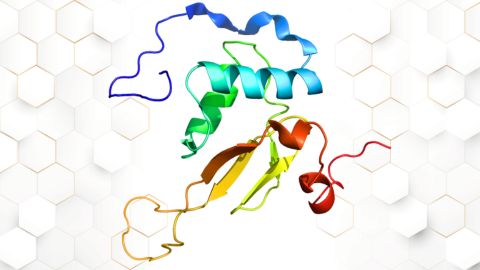

How lipogenesis works in liver steatosis. Removing protein aggregates from stressed cells. Linking plasma lipid profiles to cardiovascular health. Read about recent papers on these topics.

Small protein plays a big role in viral battles

Nef, an HIV accessory protein, manipulates protein expression in extracellular vesicles, leading to improved understanding of HIV-1 pathogenesis.

Genetics studies have a diversity problem that researchers struggle to fix

Researchers in South Carolina are trying to build a DNA database to better understand how genetics affects health risks. But they’re struggling to recruit enough Black participants.