JBC: Molecules from breast milk and seaweed suggest strategies for controlling norovirus

Norovirus is the most common cause of gastroenteritis worldwide; it causes hundreds of thousands of deaths each year and is particularly risky for children under 3 years old. If someone gets norovirus in a setting like a hospital, it’s critically important to protect others from getting infected. Research from universities in Germany, published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, suggests that it may be easier than anticipated to find a compound that could be used as a food supplement to stop the spread of norovirus in children’s hospitals.

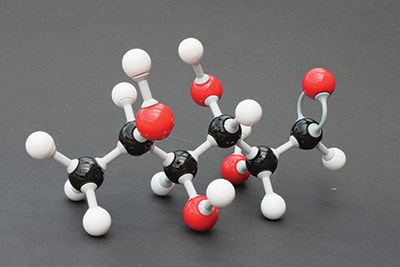

A model of a fucose molecule. Norovirus causes disease after entering cells in the gut by binding to fucose, a sugar molecule found on cell surfaces.Bim in Gartent/Wikimedia Commons

A model of a fucose molecule. Norovirus causes disease after entering cells in the gut by binding to fucose, a sugar molecule found on cell surfaces.Bim in Gartent/Wikimedia Commons

Norovirus causes disease after entering cells in the gut by binding to a sugar molecule called fucose, which is found on cell surfaces. Fucose also is found in breast milk and other foods. Norovirus can’t tell the difference between fucoses that are part of cells in the gut and those that are simply passing through; for this reason, adding a fucose-based supplement to the diet as a decoy could be a way to capture the virus and keep it from infecting cells.

To develop this strategy, however, researchers needed to understand which features of fucose and virus molecules affected how well they attach to each other. In cells, foods and milk, fucose rarely is found as a single molecule; rather, it’s part of chains or networks of sugars and proteins. Franz-Georg Hanisch, a researcher at the University of Cologne, led a project to disentangle these molecular elements and understand what kind of fucose-based product best would distract noroviruses. He started by screening the many types of fucose-containing human milk oligosaccharides, or HMOs.

To Hanisch’s surprise, the strength of the binding between the norovirus protein and HMOs did not depend much on the structure of the HMO or the types of fucose molecules it contained. Rather, what mattered was how many fucoses the HMO contained. Each individual fucose stuck weakly to the virus protein, but the more fucoses there were in the compound, the better the compound and the viral protein stuck together.

“The binding of the virus is not dependent in any way on further structural elements (of HMOs),” Hanisch said. “It’s only the terminal fucose which is recognized, and the more fucose at higher densities is presented, the better is the binding.”

Hanisch turned to the industry standard of where to get a lot of fucoses fast. Brown algae — the family of seaweed that includes kelp — produce a compound called fucoidan, which is a complex network of many fucoses. (Fucoidan has been explored independently as a treatment for HIV and other viruses for unrelated biochemical reasons.)

“There are procedures for isolating the stuff in quite high yields and in high purity,” Hanisch said.

The organization of the fucoses in fucoidans looks nothing like any fucose-containing molecules found in the human body, but fucoidan nevertheless tightly bound to the virus protein in the team’s experiments. This means fucoidan could be a safe and cheap food additive to block viruses from infecting cells. It also suggests researchers will be able to design an even better fucose-containing compound.

Hanisch and his collaborators are moving on to experiments with live viruses and live organisms, with the goal of developing a fucose-based food supplement that could be given to a group of people, such as hospitalized children, at the first sign of a norovirus outbreak, to prevent the circulating viruses from entering their cells and causing disease.

“I hope that in about three years we will have a product which can be used in norovirus defense and to go into clinical studies,” Hanisch said.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition monthly and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

New class of antimicrobials discovered in soil bacteria

Scientists have mined Streptomyces for antibiotics for nearly a century, but the newly identified umbrella toxin escaped notice.

New study finds potential targets at chromosome ends for degenerative disease prevention

UC Santa Cruz inventors of nanopore sequencing hail innovative use of their revolutionary genetic-reading technique.

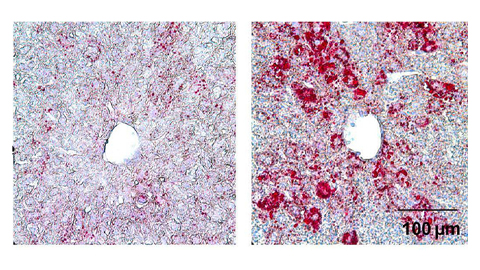

From the journals: JLR

How lipogenesis works in liver steatosis. Removing protein aggregates from stressed cells. Linking plasma lipid profiles to cardiovascular health. Read about recent papers on these topics.

Small protein plays a big role in viral battles

Nef, an HIV accessory protein, manipulates protein expression in extracellular vesicles, leading to improved understanding of HIV-1 pathogenesis.

Genetics studies have a diversity problem that researchers struggle to fix

Researchers in South Carolina are trying to build a DNA database to better understand how genetics affects health risks. But they’re struggling to recruit enough Black participants.

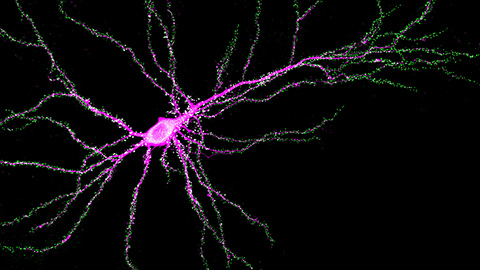

Scientists identify new function of learning and memory gene common to all mammalian brain cells

Findings in mice may steer search for therapies to treat brain developmental disorders in children with SYNGAP1 gene mutations.

.jpg?lang=en-US&width=300&height=300&ext=.jpg)