JBC: Bacterial drug synergies hide in plain sight

Rapamycin is named for Rapa Nui, or Easter Island, where the bacteria that produce it were initially isolated. HULEROY0/PIXABAY

Rapamycin is named for Rapa Nui, or Easter Island, where the bacteria that produce it were initially isolated. HULEROY0/PIXABAY

While on the hunt for a molecule with therapeutic potential, Peter Mrak and his colleagues made a more sweeping discovery: Every known isolate of bacteria that produces the immunosuppressive drug rapamycin also can make a second compound that enhances rapamycin’s effect.

“Put into simple words, this feels like finding an ancient treasure map in your grandfather’s attic,” Mrak said.

Rapamycin was isolated in the 1970s from bacteria found on Easter Island. The molecule gives those bacteria a competitive edge by suppressing the growth of fungi in the soil. At first, researchers took a cue from nature and tried using rapamycin to treat fungal infections. Then they found that it also suppresses growth and metabolism in human cells, notably those of the immune system. The drug is now used to prevent transplant rejection and stop tissues from growing into coronary stents.

Mrak and an international team at the Swiss pharmaceutical company Novartis recently sought other beneficial compounds from the same bacteria. Mining for natural products with pharmaceutical potential in bacteria from diverse environments is a standard approach with high success rates. But in this case, the researchers found more than a single molecule.

In culture media that had been used to grow a rapamycin-producing strain of Streptomyces, the scientists found a group of secondary products called actinoplanic acids. This family of molecules had been isolated from other microbes in the late 1990s, but no one had worked out how they are synthesized. Mrak and colleagues noticed that actinoplanic acids contain a chemical group called a tricarballylate that would be very difficult for a synthetic chemist to produce in the lab and wondered whether they could exploit bacterial means of synthesizing that chemical group.

The researchers used a bioinformatics tool called antiSMASH to comb through the Streptomyces genome, hunting for possible enzymes involved in actinoplanic acid production. After finding a few candidates, they showed by targeted mutagenesis that a cluster of closely spaced genes on the Steptomyces genome can function as a sort of biochemical assembly line to generate actinoplanic acids, including making the tricky tricarballylate.

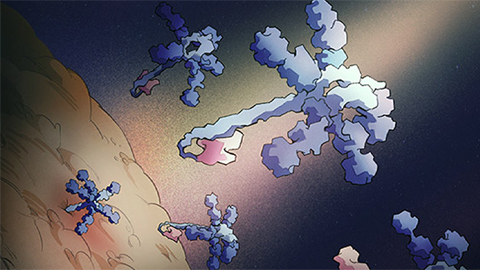

When Mrak and colleagues looked for other bacteria that might carry this gene cluster, they noticed something surprising. Every one of the fully sequenced bacterial isolates known to make rapamycin also carried the genes to make actinoplanic acid. This suggested that microbes might benefit from having both molecules.

When the researchers tested actinoplanic acid and rapamycin as fungal growth inhibitors, they found that the two molecules’ combined effect was greater than you’d expect from simple addition. In other words, the molecules work synergistically. The research appears in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Doctors have found by trial and error that the effect of rapamycin in patients is amplified when the drug is combined with molecules that, like actinoplanic acid, inhibit an enzyme called farnesyltransferase. That combination of drugs is in clinical tests for cancer now. The authors say their approach could be used to find other co-occurring groups of biosynthetic genes more rapidly.

“We could potentially shorten the path toward new therapies by learning from examples which have evolved in nature over millions of years,” Mrak said. “Considering that some (natural products) show their best only in combination with another molecule, there may be a number of new medicinal compounds hiding among the natural products already discovered.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition monthly and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

What is metabolism

A biochemist explains how different people convert energy differently – and why that matters for your health.

What’s next in the Ozempic era

Diabetes, weight loss and now heart health: A new family of drugs is changing the way scientists are thinking about obesity — and more uses are on the horizon.

How a gene spurs tooth development

University of Iowa researchers find a clue in a rare genetic disorder’s missing chromosome.

New class of antimicrobials discovered in soil bacteria

Scientists have mined Streptomyces for antibiotics for nearly a century, but the newly identified umbrella toxin escaped notice.

New study finds potential targets at chromosome ends for degenerative disease prevention

UC Santa Cruz inventors of nanopore sequencing hail innovative use of their revolutionary genetic-reading technique.

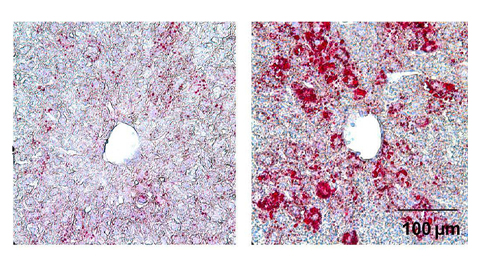

From the journals: JLR

How lipogenesis works in liver steatosis. Removing protein aggregates from stressed cells. Linking plasma lipid profiles to cardiovascular health. Read about recent papers on these topics.